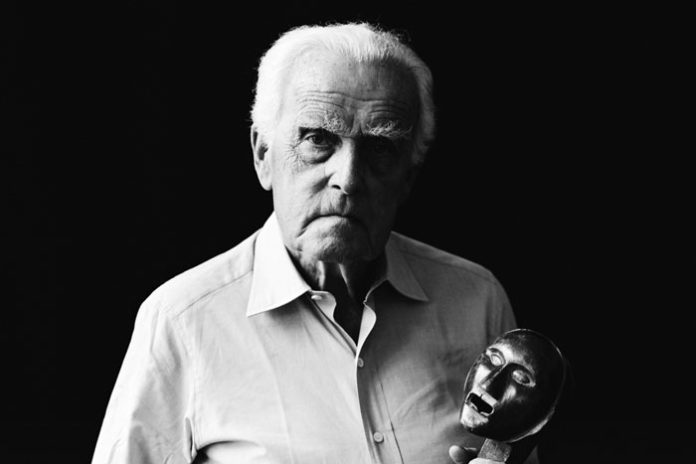

Edmund Carpenter, an archaeologist and anthropologist who, impatient with traditional boundaries between disciplines, did groundbreaking work in anthropological filmmaking and ethnomusicology and, with his friend Marshall McLuhan, laid the foundations of modern media studies, died on July 1 in Southampton, N.Y. He was 88.

His death was confirmed by his wife, Adelaide de Menil.

Mr. Carpenter, a disciple of the anthropologist Frank Speck, started out excavating prehistoric Indian sites in the Northeast but soon showed signs of the intellectual restlessness that marked his entire career.

At a time when few anthropologists showed much interest in the Arctic and its peoples, he embarked on a series of expeditions among the Aivilik people and published several books on the Inuit: “Time/Space Concepts of the Aivilik” (1955), “Anerca” (1959) and “Eskimo” (1959), republished as “Eskimo Realities” in 1973.

His interest in language and culture led him into a fruitful collaboration with McLuhan when both taught at the University of Toronto in the 1950s. Together they organized the influential Seminar on Culture and Communication to discuss the role of radio, television, film and print in transforming human relations.

Continue reading the main story

Mr. Carpenter took the lead in editing Explorations, the interdisciplinary journal that grew out of the seminar; it published writers like the anthropologist Dorothy Lee and the literary critic Northrop Frye.

In 1969, he and Ms. De Menil, a photographer whom he would later marry and a member of the family that founded the Menil Collection in Houston, went to Papua New Guinea to observe the effects of modern communications on tribal peoples. Invited by the Australian government, he accepted the post of research professor at the University of Papua New Guinea because it offered “an unparalleled opportunity to step in and out of 10,000 years of media history, observing, probing, testing,” he wrote in “Oh, What a Blow That Phantom Gave Me!” (1972), his best-known book. “I wanted to observe, for example, what happens when a person — for the first time — sees himself in a mirror, in a photograph, on films, hears his voice; sees his name.”

He was deeply skeptical about scientific claims of impartiality and worried about the destructive effects of modern life on tribal peoples. Although he continued to teach anthropology and supported numerous ethnographic filmmakers through the Rock Foundation, a charity set up by his wife, he disengaged from the profession.

He taught intermittently in the United States and spent eight years at the Museum of Ethnology in Basel editing the papers of the art historian Carl Schuster, which were published in 12 volumes as “Social Symbolism in Ancient and Tribal Art: A Record of Tradition and Continuity” in the late 1980s and in a one-volume condensation, “Patterns That Connect: Social Symbolism in Ancient & Tribal Art.”

Edmund Snow Carpenter, known as Ted, was born on Sept. 2, 1922, in Rochester. As a boy he dug for artifacts at the family’s summer home on Gull Lake, Mich. At 13 he met Arthur C. Parker, a Seneca anthropologist and director of the Rochester Museum and Science Center, who invited him to take part in excavations of prehistoric Iroquoian sites in the Upper Allegheny Valley.

He enrolled at the University of Pennsylvania in 1940 to study with Speck but joined the Marines a few months after Pearl Harbor. He saw action in New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, the Marianas and Iwo Jima. After the war ended, he was assigned to oversee several hundred Japanese prisoners, whom he put to work on an archaeological dig in Tumin Bay, Guam.

After being discharged from the Marines in 1946 with the rank of captain, he returned to the University of Pennsylvania, which awarded him a bachelor’s degree. He received a doctorate in 1950, writing his dissertation on the prehistory of the Northeast.

At the University of Toronto, where he began teaching in 1948, he became entranced by what he later called “the nonsensory spirit world of electronic media.”

His collaborations with McLuhan included numerous jointly written articles and the anthology “Explorations in Communication” (1960). The article “Fashion Is Language,” which appeared under McLuhan’s name in a special McLuhan issue of Harper’s Bazaar in 1968, was actually written by Mr. Carpenter after McLuhan went into the hospital for brain surgery. It was published in book form, in 1970, under Mr. Carpenter’s name, with the title “They Became What They Beheld.”

Mr. Carpenter was deeply involved in the writing of “Understanding Media,” the book that made McLuhan an intellectual celebrity. It began as a collaboration, but Mr. Carpenter gradually withdrew and the book was published under McLuhan’s name alone. “I admired Marshall’s insights and style, but it simply wasn’t me,” Mr. Carpenter wrote to the anthropologists Harald E. L. Prins and John Bishop in 2002. The published work was a hybrid. “The final version of ‘Understanding Media’ mixed both our contributions,” he wrote in a 2001 essay. “This partly explains its uneven tone.”

Mr. Carpenter, who had done innovative programs on tribal art for Canadian radio and television, found wider scope for filmmaking at San Fernando Valley State College (now California State University, Northridge), where he was invited to found an experimental joint program of anthropology and art, with a special focus on anthropological film. With the folklorist Bess Lomax Hawes and others, he filmed the Georgia Sea Island Singers performing traditional Gullah songs and dances.

After returning from Papua New Guinea, Mr. Carpenter taught at the New School for Social Research in Manhattan, Adelphi University on Long Island and Harvard’s Center for Visual Anthropology.

Mr. Carpenter lived in Manhattan and Sag Harbor, N.Y. In addition to his third wife, Adelaide, known as Addie, he is survived by three sons, Stephen, of Columbia Station, Ohio; Rhys, of Pittsboro, N.C.; and Ian, of Astoria, Queens, and a sister, Barbara Grace, of Rochester.

He helped organize two shows now at the Menil Collection: “Upside Down: Arctic Realities,” an exhibition of ancient Arctic art, and “The Whole World Was Watching: Civil Rights Era Photographs From Edmund Carpenter and Adelaide de Menil.”